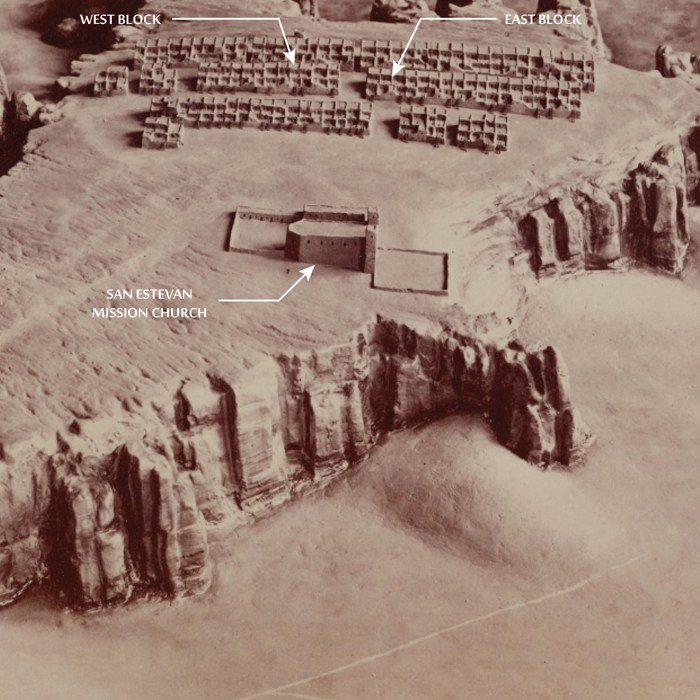

Acoma was first documented in European historic records in 1539 by the Coronado expedition, followed by several other emissaries from Spain, until the village was visited finally by Juan de Oñate in 1598. At the time, the only way onto the mesa was to climb a large crevice in the rock with hand- and toe-holds carved into the rock. Early Spanish period reports indicated that the village of Ha-cu-que, Ah-co, Ako, or Acoma was constructed of 200 houses. The original village on this site was stacked a little like blocks, forming a D-shape several layers tall. Other ancient cities in the Southwest, such as Taos Pueblo and the ruins at Chaco Canyon and Bandelier National Monuments, have a similar structure.

The Acoma people found out that Oñate had a plan to colonize their homeland, to take their food and force their people into slavery as he had done at other pueblos. Acoma decided to fight, and in 1598, residents fought and killed a group of soldiers coming to take their freedom. This had terrible consequences two months later, in January 1599, when Spanish soldiers returned to avenge the attack, and they brought many more soldiers and cannons. They attacked the elevated city, and the battle lasted three days. Hundreds of the Acoma people were killed and their entire village was destroyed.

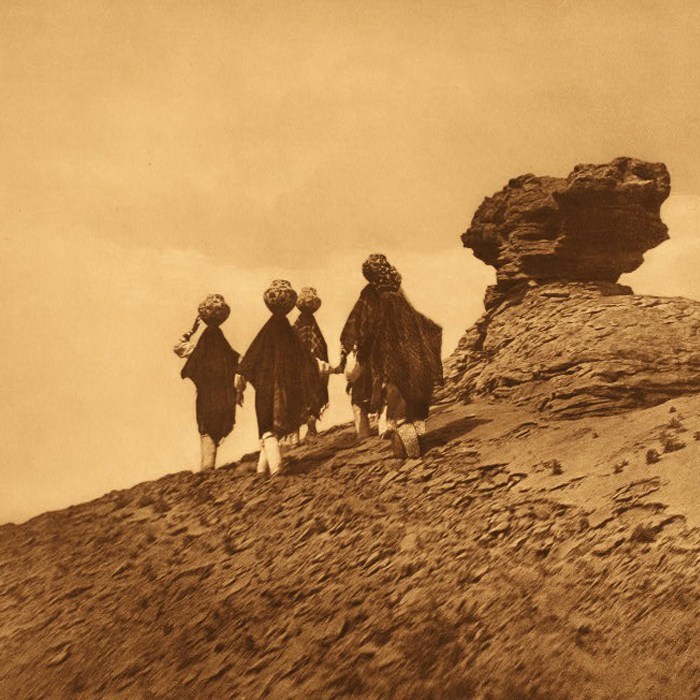

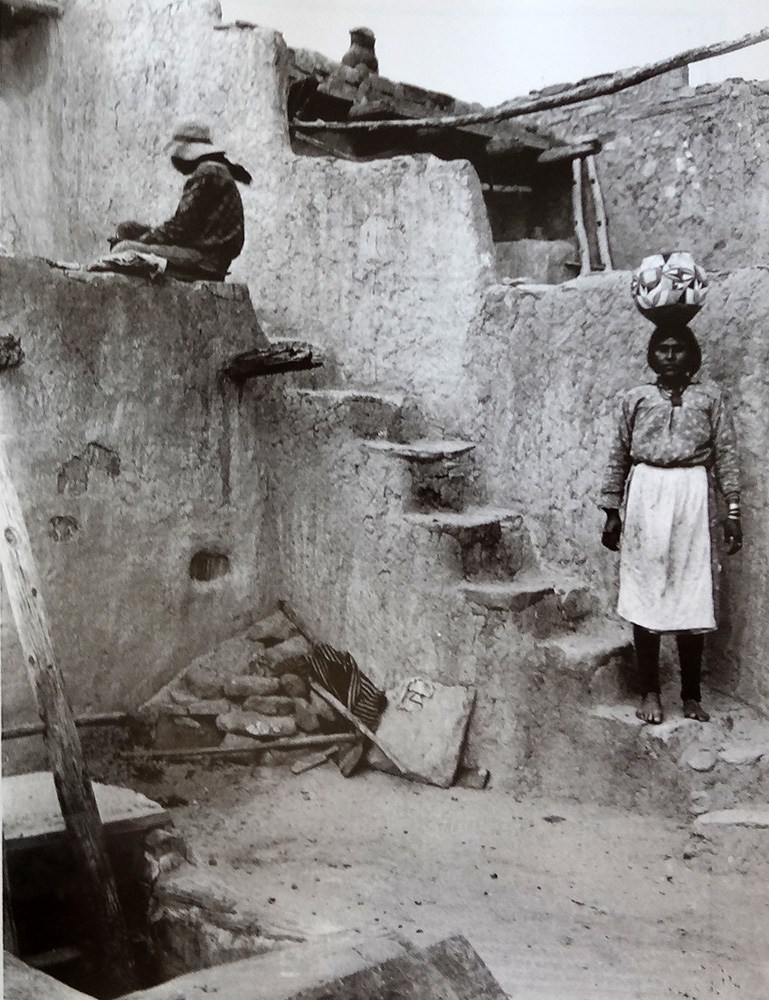

As Acoma was very remote, what we know about its rebuilding mostly comes from writings from visitors to the Spanish mission that was established many years after Acoma stood up for themselves. It was in the late 19th century and early 20th century when New Mexico became and American territory and then state, and when the railroads were built and brought all kinds of new people and technologies to New Mexico, that we start seeing the first visual insights into Acoma and other Southwest villages through drawings, photography, articles, and books.

In 1877, photographer William Henry Jackson, who helped establish Yellowstone National Park, came to Acoma and documented the village. He built models of Acoma, Taos, Mesa Verde and Pueblo Bonito at Chaco Canyon to showcase the West at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. This moment marked the beginning of the most significant change to Acoma’s future from outside forces. It was the moment Acoma became a tourist destination. Acoma became even more of an intriguing destination when photographer and journalist Charles Lummis published the stories of his travels with Adolph Bandelier to Acoma and many other Pueblo sites just a few years later. His description of an Acoma home is charming:

“The dark store-rooms of their curious houses are never empty; and in the living-rooms hang queer tasajos (twists) of dried muskmelon for dwarf pies, bags of dried peaches for the same end, jerked mutton from their own flocks, jerked venison from the communal hunt, parched chile, and other staples. In a corner is always the row of sloping lava slabs, neatly boxed about, whereon blue corn is rubbed to meal with a smaller slab. Along the walls hang buckskins and Moqui [Hopi]-woven mantas, cougar-skin bow cases beside the Winchester, coral necklaces and solid silver necklaces, the work of their own clever smiths, and many other aboriginal treasures. The cleanly and comfortable wool mattresses are rolled and laid on benches with handsome and often costly Navajo blankets, for a daytime sofa. By night they are unrolled upon rugs or canvasses on the floor. In one corner is the wee but effective adobe fireplace, with chimney generally of unbottomed earthen jars, and in another row of handsome tinajas, painted in strange patterns, full of fresh water.”

But even as Acoma was becoming of greater interest to the outside world, its traditions were being undermined. In the 1920s and 1930s, the young people of the Pueblo were sent to Indian Schools, where they were not allowed to speak their own language or learn their own ways. This resulted in a loss of cultural building knowledge, at the same time that the Keres language was nearly lost, and the knowledge of Acoma traditional weaving was totally lost. The Americans also started importing new materials and technologies into traditional New Mexican earth architecture around this time. These new materials, like metal windows and roofs, glass windows and cement stucco, were supposed to be easier to install and maintain, but these ultra-strong modern materials and their soft earthen counterparts in the historic pueblo don’t always work well together. And, the people… that maintained and kept the buildings “alive”… seemed to be forgotten in architecture.

In 1965, renowned architectural historian Bainbridge Bunting described Acoma’s historic village as “the most important example of town planning and architectural achievement among the Western Pueblo Indians.” Acoma is indeed extremely special, as it is the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States!

A Different Way of Seeing Preservation #

Santa Clara Pueblo member Rina Swentzell was an expert on Puebloan architecture. She spent her life re-weaving the story of the people back into the way we look at Puebloan architecture.

She argued that buildings are like living beings, and that they change over time, just as people do, as families do, and as our communities do. She recognized and taught about the interconnection between the people and the buildings.

In her essay Pueblo Structures and Worldview, Rina wrote about how the children in the Pueblos would often lick the walls of the buildings to taste where they came from, as the adobe would taste different based on the source of the clay. One of her favorite tasting homes developed a crack that she watched get worse over many weeks and months, and when she asked her mother why nothing was being done, her mother replied, “That house has had a good life. It has been fed blessed and healed… it is now time for it to go back into the earth.” The life force, what her people call the po-wa-ha, that exists in humans, animals, and plants, is also contained in buildings. Sometimes, in traditional cultures, buildings are allowed to die.