An archaeologist named Reynold J. Ruppé, Jr. conducted digs at parts of the ruins of the Spanish-destroyed village in the 20th century. His team unearthed the older village’s walls, and discovered they were made of long pieces of sandstone and covered with an earth plaster of red and white pigments from the area’s landscape. Later walls from the dig site were a combination of adobe and sandstone. The community was built in blocks of houses which ran from east to west, and each house was between one and five rooms deep.

Like the older village ruins, the oldest sections of the current village, which started being built in 1646, consists of one-, two-, and three-story houses that run from east to west. But in the newer village, the rows of houses were arranged in 3 lines, and each block of homes was oriented slightly to the southeast. This method of laying out the homes is an important element of controlling the sun… it allows us to keep the sun out in summer when it is hot and to catch the sun early in the morning in winter when it is cold. The houseblocks are broken into sections by a ceremonial plaza as well as small pathways or “slots” which mimic similar gaps in the sandstone landscape around the village. The alignment of the streets to the east and west frames views to sacred sites and mountains in those directions, and also allows the observation of celestial alignments of stars, star clusters, and planets that coordinate with seasonal festivals, planting times, and ceremonies.

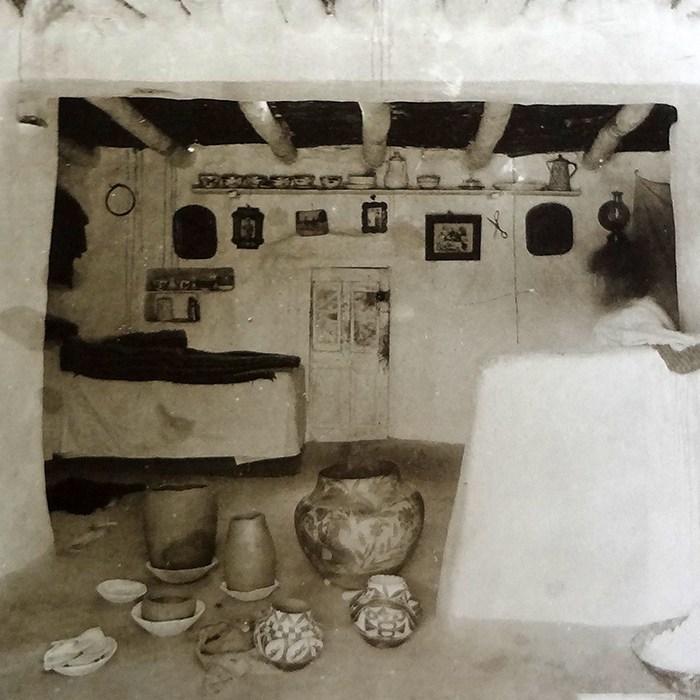

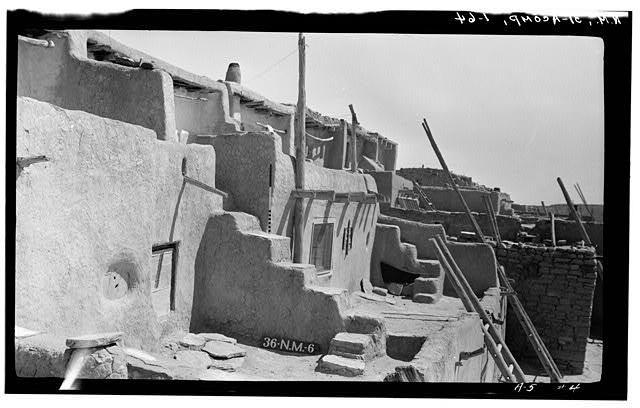

The homes are stacked like a wedding cake, with the tallest side to the north. The terraces naturally collect heat from the sun in the south and block the wind from the north in the winter. Some experts believe that the south-facing structures are related to those built by Acoma’s ancestors at Mesa Verde. The bottom level of the home is usually built of stone, and the second and third floors are built of adobe. The 2-foot-deep dirt roof and ceiling are held up with round wooden vigas (roof beams) and wooden planks or latillas (branches).

The dirt and clay used for adobes in the 1640s village was harvested from right around the mesa, as well as from middens, an archaeological term for “waste piles,” located around the site. The use of midden soil for adobes was likely pioneered by the first priest of Acoma’s Mission San Esteban del Rey, Fray Juan Ramirez. Because of the use of midden soil, the adobes might include bones, charcoal, potsherds, or yucca… all things we would find in a midden, and so the building blocks themselves are something of a miniature archaeological site. Newer buildings are also commonly constructed of salvaged adobe, potsherds, and stone from older buildings. Rebuilding using local and available materials is how Acoma has remained sustainable over many hundreds of years.

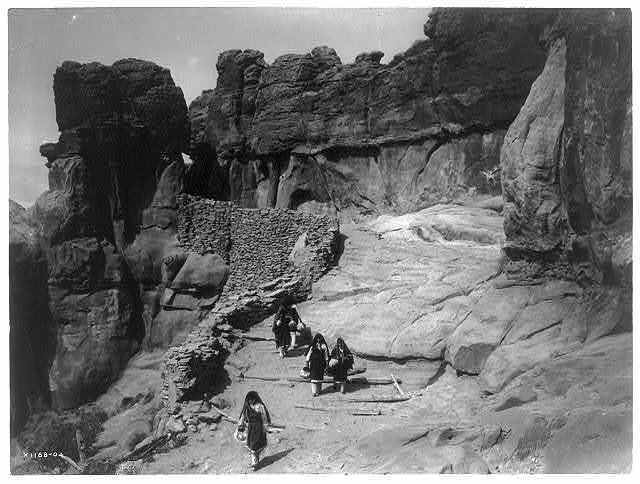

Before the roads were built just a few decades ago, the materials used to construct the village were carried up the cliffs in hand-made baskets or buffalo-hide bags carried like a backpack. Men would build the foundation and walls of the home, and installed the vigas and roofs. Women did the plastering, flooring, built the chimneys, and designed the spaces.

Before the time of the Spanish, Acoma’s roofs had skylights to allow light in and smoke from the open interior fire out. When they had to rebuild the village, they used the Spanish version of fogon, or fireplaces, and chiflon, or chimney vents.

Prior to the late 1800s, windows in structures throughout the southwest were small because the earliest peoples here would cover them with a weaving, animal hide, or a translucent stone like mica. There were no doors at the ground level because attacks from rival tribes were not uncommon. Residents accessed their homes by climbing to the tall first floor roof on a ladder at the south, which could be raised in case of attack. They then climbed a stepped wall to the third floor, where they entered the main home and climbed back down to the other levels by ladders inside. This is unique, as most other pueblos, including the other western tribes at Zuni and Hopi, were accessed from the second floor. The lower floor was used for storage. (Once upon a time, it was common for Acoma families to have three years’ worth of food stored in case of emergency or drought!!) The second floor was a living space, and the third floor was the main entrance as well as bedroom.

With the arrival of the railroads, life would be forever altered throughout the New Mexican Territory. With railroads came trade, tourism, and supplies from the east and eventually, west – including milled lumber, glass windows, doors, stovepipes, nails, and locks, as well as paints and finishes that could now be bought at a mercantile or hardware store.

In the 20th century, with less likelihood of attack and people leaving the mesa’s old village to be closer to work and summer gardens, came some of the other significant architectural changes at Acoma… by the 1920s, windows and doors were added to first floors. Also, everyone but the War Chiefs and other families required to live in the historic village for ceremonial purposes had moved from the mesa to the outlier villages closer to work and their summer farms near the river. In the years since, Acoma’s historic village has been transformed into more of a ceremonial space than a living space. Most families go there for special events and ceremonies. They usually do not stay for more than a week or two at a time on the mesa. This has resulted in making it harder to maintain the village, as families now have to maintain both their homes closer to town as well as the historic homes on the mesa.