The roots of Acoma Pueblo extend deep and wide across the ancient American Southwest, including the magnificent sites of the Chaco Canyon National Historical Park. Let’s explore the wonders of Chaco, it’s connections to Acoma, and how both sites exemplify the deep roots of sustainability in New Mexico.

Chaco Canyon is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that preserves the history and culture of the Pueblo people. Chaco Canyon is the ancestral home of Pueblo people and it is where many of the cultural traditions that are practiced to this day at Acoma, Zuni, Tesuque, Zia, Hopi, Taos, and other pueblos emerged. Chaco’s magnificent great houses – Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, and others – still tower over the canyon floor, while in the surrounding landscape, ancient roads and pathways to outlying villages and shrines offer silent testimony to the wonders of Chacoan society.

Chaco Canyon was chosen as a place to live for a variety of reasons. From the time of the first Basketmaker villages in Chaco, Pueblo people lived there because it offered the abundant resources necessary to live a quality life – plants for food and medicine, arable land for agriculture, clay for pottery, stone for tools and building houses, wood for building, and water. Less tangible but no less important reasons to call it home include Chaco’s landscape and topography and what we believe is the spiritual quality of Chaco Canyon.

Three of the great houses in Chaco Canyon (Pueblo Bonito, Penasco Blanco, and Una Vida) were built beginning in the early 800s after Pueblo people had lived in the area for hundreds of years. These pueblos were built in prime agricultural locations from east to west across Chaco Canyon. They were faced south and east to maximize solar gain. Although these great house structures began as relatively small buildings (50 rooms or thereabouts), over time they grew, with rooms and stories added. Pueblo buildings are typically terraced, with upper stories built above and back from lower stories. This building style allowed the ancient Chacoans to maximize their solar gain across all levels of their pueblos.

By AD 950, Chaco Canyon had emerged as one of the most important ritual centers in the ancient Puebloan world. By 1060, the cluster of structures in what has been termed “downtown” Chaco–the immediate vicinity of Pueblo Bonito was laid out and largely constructed. Within about a square kilometer were four great houses–Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, Pueblo del Arroyo, and Pueblo Alto, along with numerous small house pueblos, and the stand-alone great kiva at Casa Rinconada.

As part of Chacoan society’s growth after AD 1050, many miles of roads were built across the region, linking great house sites, shrines, smaller pueblos, and important, natural landscape monuments. Development of Chaco’s Great North Road occurred after AD 1050 and all of the northern Chacoan outliers were built after AD 1075.

By AD 1090, northern Chacoan outliers at Salmon Ruins, Chimney Rock, Wallace, Lowry, and Morris 41 (and several other sites) were built and occupied. The east and west pueblos at Aztec were built between AD 1105 and 1125. This northern shift of focus, of people, and perhaps, of ceremonial importance, was complete by AD 1110-1125, when Aztec emerged as the largest Chacoan complex and the successor to Pueblo Bonito’s role in Chacoan society.

By the late eleventh century, then, the unique nature of Chacoan society had emerged across what is now the Four Corners region. Chaco ritual was, by this time, “proven” and the appeal of the Chacoan ceremonial system rapidly expanded. As a result, more and more people came into Chaco, some to try to settle and others to participate in periodic ceremonies.

Acoma Pueblo’s people (and those of other pueblos) migrated through the sites of Chaco Canyon and the Chacoan World as they moved across the landscape. Ultimately, folks came to the mesa and called Haak’u their new home.

Correlating the essential elements at Acoma and Chaco #

At least five of Acoma’s essential materials and forms were also found in Chaco – stone, mud, wood, corn, and pottery. Archaeologists have not found evidence of the use of mica for windows in Chaco’s great houses or small pueblos.

Chacoan Connection to the Landscape + Water #

The Chacoans grew corn, beans, and squash in large quantities in Chaco Canyon. Fields were planted in the floodplain and received water during rains. Other fields were put on terraces above the floodplain and water with a technique called pot irrigation – pots filled at a water source and carried by hand. Yet other fields were planted in upland settings and used runoff water.

The Chacoans built ditches, ponds, and other features to manage and store water. The north side of the Canyon had a very sophisticated water collection system that collected the water that poured off the steep canyon walls during rainstorms.

Soils is Chaco Canyon were of sufficient quality to allow the Chacoans to grow most or all of the food they needed. They also hunted large and small game and gathered a large variety of wild plants for food.

Chacoan Use of Stone #

The stone used to build Chaco’s great houses was quarried at locations in the Canyon and some areas outside. One of the factors that drew Pueblo people to Chaco Canyon was the abundant, tabular sandstone present. Chacoan great houses contained more than 20 million pieces of sandstone! Much of this material was very fine and tabular in shape, and took painstaking skill to assemble into walls, rooms, and pueblos.

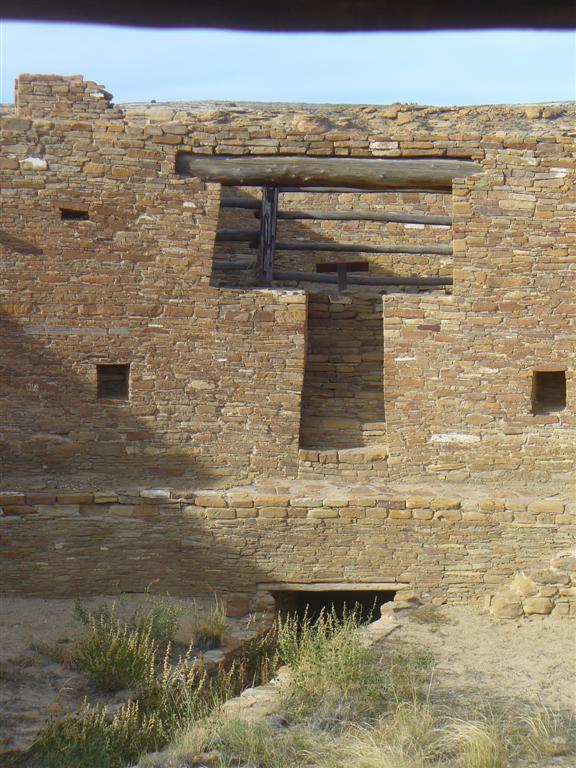

Chacoan great houses were built with a variety of stone veneer patterns. Archaeologists have identified six or seven of these styles and they seem to be time-sensitive in Chaco Canyon. That is to say, Type I masonry is the earliest and was succeeded by Type II. These styles made variable use of different stone types – some include mostly thin tabular slabs while others made use of larger, brick-sized stone. It is unclear how and why these veneers styles changed through in Chaco. Some change may be related to the exhaustion of some masonry quarries in the Canyon that required a shift in type of stone use. The tabular style of masonry was preferred early in Chaco’s history and this type of stone may simple have been largely depleted in the Canyon, requiring longer and longer trips to find the necessary stone.

The other possibility is that different groups of masons in Chaco simply trained in building different styles. This would have resulted in the variety of stone veneer patterns seen in the walls of Chacoan great houses. In this view, these masons worked within specific learning traditions that were perhaps similar to guilds in other parts of the world.

Chacoan great houses were built with tens of thousands of trees and tree limbs harvested from a variety of locations. Chemical sourcing work shows that a good percentage of the wood used to built Chaco’s amazing architecture came from the Chuska Mountains (50 miles to the west of Chaco) and the forests around Mt. Taylor (some 55 miles to the south-southeast of Chaco). These high-elevation timbers included ponderosa pine, white fir, douglas fir, spruce varieties, and aspen (rare). A good percentage of local wood was used as well including pinon, juniper, douglas fir (from locations 10-15 east of Chaco) and cottonwood (rare).

# Chacoan Ethnobotany

The ancient Chacoans used a great variety of natural plants found in the Canyon. Plants used for food and medicine included goosefoot, pigweed, purslane, beeweed, bugseed, winged pigweed, tansy mustard, sunflower, stickleaf, tobacco, groundcherry, globemallow, wild potato, ricegrass, dropseed, hedgehog cactus, prickly pear, yucca, walnut, juniper, pinon, sumac, saltbush, wild grape, horsetail, rush, reed, sedge family, and cattails.

# Chacoan Corner Windows

Pueblo Bonito has several corner windows intentionally built into rooms. Two of these windows face east and were built to view the sunrise on the winter solstice… this is why they are now called “solstice windows”.

# Chacoan T-shaped doors

Researchers have debated Chaco’s T-shaped doors for more than a century. Although some have suggested that these features were intended to allow people with wide burdens to pass more easily through different rooms in Pueblo Bonito and other great houses, analysis has shown that the T-shaped doorways were not built with this purpose in mind. While it would be incorrect to say that these doors are randomly spread across Chacoan great houses, it is true that they have limited occurrences. Because of this finding, many archaeologists infer that the T-shaped doorways had a ceremonial purpose. At the site of Salmon Pueblo, a Chacoan Outlier north of Chaco on the San Juan River, all of the original T-shaped were built in exterior room walls in rooms that faced the plaza. Thus, we can suggest that these doorways were portals that allowed residents to pass from “inside,” private space to “outside,” public space.

Our deepest thanks to contributor, archaeologist Paul Reed, for this assessment!!!

Paul Reed is a Preservation Archaeologist with the Tucson, Arizona-based non-profit Archaeology Southwest and works as a Chaco Scholar at Salmon Ruins, New Mexico. Reed has been employed in this position for 16 years. Reed’s most recent writing is a book co-edited with Gary M. Brown entitled Aztec, Salmon, and the Pueblo Heartland of the Middle San Juan, to be published in SAR Press’ Popular Series in the summer of 2018. He also served as both editor and contributing author on Chaco’s Northern Prodigies: Salmon, Aztec, and the Ascendancy of the Middle San Juan Region After AD 1100, published by the University of Utah Press (2008). Reed was also editor and author of several chapters of the three-volume, comprehensive report entitled Thirty-Five Years of Archaeological Research at Salmon Ruins, New Mexico published in 2006 by the Center and the Salmon Ruins Museum. His other books — The Puebloan Society of Chaco Canyon and Foundations of Anasazi Culture (as editor) — have explored the origins of Pueblo culture and Chaco Canyon.

During the last four years, Reed has been working to protect the Greater Chaco Landscape from the effects of expanded oil-gas development associated with fracking in the Mancos Shale formation. Through a series of meetings and forums with public officials, Tribal leaders, various US Government agencies, and New Mexico’s Congressional delegation, Archaeology Southwest and its partners have focused on expanding protections to sites, traditional cultural places, and fragile landscapes in the greater San Juan Basin.