Respect for the Landscape #

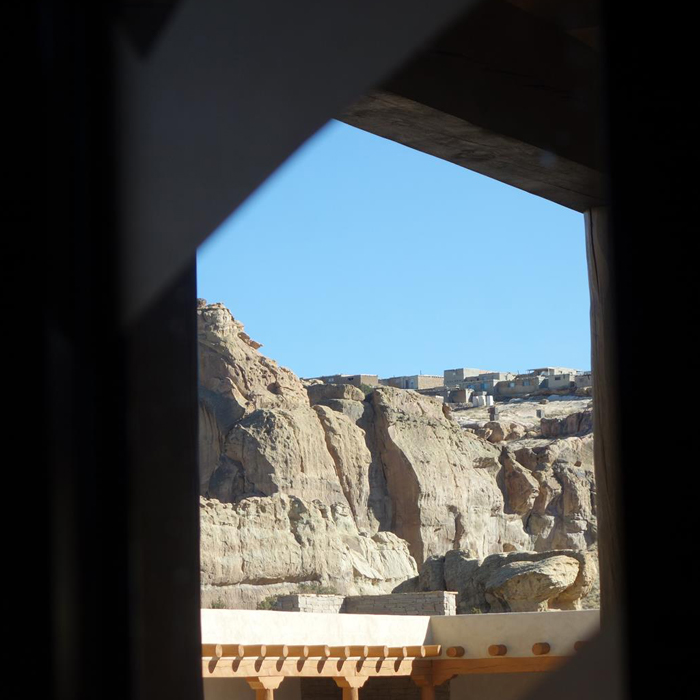

The landscape is an essential part of the relationship between Acoma’s people and their place. The buildings within and around the historic village respond directly to the land. The landscape is also seen as part of the experience of visiting Acoma. The goal is to get people who just came off the highway from the fast modern world… to slow down so they can really experience this unique place, its landscape, architecture, and people. The drive into Acoma is similar to the route that the people of Acoma took when they migrated to this place from points north. Experiencing that sense of coming home was essential in the design of the Cultural Center. Entering the Cultural Center from the north, a great window opens up to a view of the historic village on the mesa, and we know we have arrived.

Water #

One of many aspects of sustainability that we pay close attention to in design today is access to water. Water is critical, not only for drinking and cleaning, but also for sustainable agriculture and food production. As Acoma has no natural running water sources, natural depressions in the rock (sometimes with man-made walls to help) have been used for many hundreds of years to collect water and snow at both the top and base of the mesa. Obtaining water has always been an essential aspect of living on the mesa, as photographer Edward Curtis captured in his photographs of elegant Acoma women gathering it in beautiful pottery jars at the turn of the last century.

When it came time to design the Cultural Center, tribal elders determined that they did NOT want to do what most sustainability experts would tell them to do – capture the water that landed on the roof in metal or plastic cisterns for later use. Rather, they wanted to water to be allowed to fall, move from the building to the landscape, and be absorbed back into the earth to recharge the aquifer and feed the landscape around the building. To the Acoma people, water is alive. Allowing it to remain free and alive is more important than saving it to use later. It would also require sophisticated and expensive systems to clean the water to make it safe for human consumption. They decided that using technology to solve a problem that actually created more problems was not a truly sustainable solution. There is wisdom in this approach.

Slots #

Slots in the sandstone landscape around Acoma are echoed in the village as well as in the Cultural Center. In the historic village, one primary slot orients from the main ceremonial plaza directly to Mount Taylor. Others seem to be just small spaces left between buildings.

In the cultural center, slots are used to break up the large building, as well as, in the case of the great east-west running slot at the museum, to tell the story of Acoma’s sacred connection to the stars of the Milky Way, and the east-west alignment of the village to the movement of the sun.

Environmentally Adaptive Design #

The Sky City Cultural Center and Acoma’s historic village are built to respond to adapt to the climate of high solar radiation, low humidity and little precipitation, moderate to high winds, and big temperature swings from day to night. Building on the high precipice of the mesa allows the village to be up in the layer of the atmosphere where the summer breezes are best. The way the buildings are arranged blocks the winter winds from the northwest with the high walls of the multi-story sections, and that also captures the summer breezes.

The high north walls have very few, and very small openings, if they have any at all. That minimizes the cold air infiltrating the building in winter. The doors are often raised a foot or so above the ground plane, rather than having an entry flush to the ground outside. This helps hold in heat. As well, the shared walls between homes allows heat and coolness to radiate through the spaces more evenly. Interconnecting rooms, and their aligned openings from front to back of the structure, improves ventilation, cooling, heating, and lighting. Using the coldest rooms on the first floor for storage means materials and foods last longer.

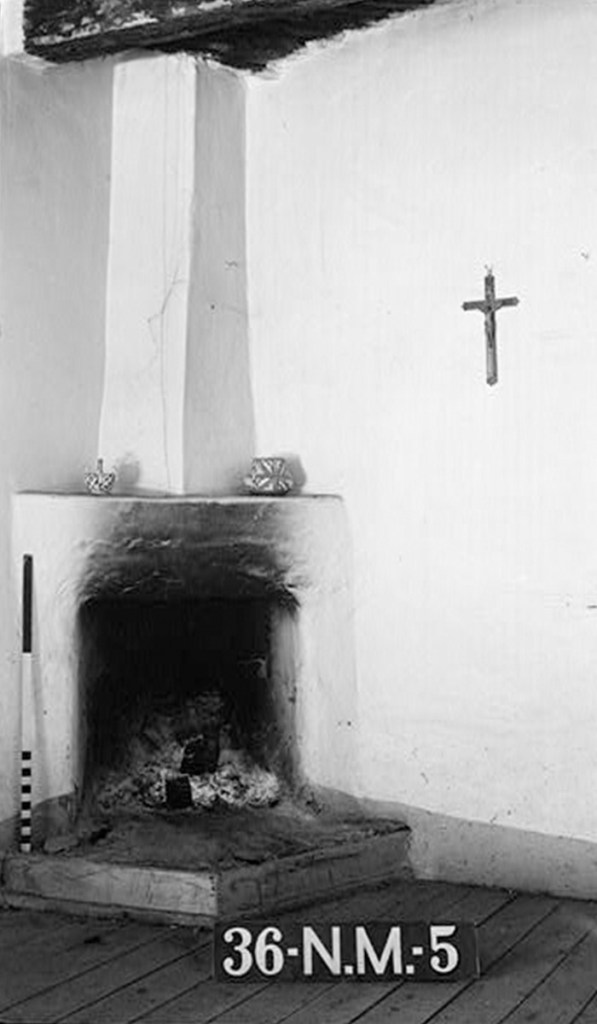

Fireplaces on interior walls prevent the heat stored in the masonry flue from being lost to the outside. Instead, your neighbors benefit from the heat produced. The main living areas are located in the south, and have larger openings to the outside, so those rooms are warm and full of light.

Light paint and earth stuccos used inside the homes reflects natural light back into the depths of the structures. The central plaza, a space for dance, ceremony, and community gathering, is located such that it is sheltered from the worst of the winds.

Even building houses to the north and west of the natural pools helps the Acoma people adapt to their environment… by building this windscreen between the wind (from the northwest) and the water, they minimize evaporation so the water is available to use for much longer.

The rows of houses at Acoma are oriented such that the one row does not cast shade on another and deeply inset doors and windows provide their own shade in the summer when the sun is directly overhead. As well, overhangs at the roof parapets offer even more shade and a little place to stand outside but be mostly protected when it rains. Acoma’s terraces, orientation, and very thick walls act as thermal mass storage devices, which releases heat slowly in winter, and mostly keeps the heat out in summer.

When University of Southern California professor and solar researcher Ralph L. Knowles had his students model Acoma for a study on energy efficiency in the late 1970’s, they identified “a significant relation between the building arrangement and the sun.” The Pueblo’s design absorbed solar radiation on the southern exposure, which would radiate into the interior rooms at night. This natural heating method would be assisted with the use of a small fireplace, which would keep the rooms at a comfortable temperature while using only a small amount of wood.

At the Cultural Center, the façade faces north, which puts it in the shade most of the summer, making it a cool entry for when the center is open in spring, summer, and fall. As well, the east and west wings of the building protect the south courtyard from winds, and masonry walls, shade structures, and protected windows minimize solar gain in summer when too much heat is a problem, but also allow the sun in to maximize solar gain in the winter when additional heat is helpful and the sun is low.

Terraces #

The stepped terraces of Acoma’s village and cultural center are an element of passive solar design. The sun naturally warms up the southern faces and roofs of the terraced buildings. The walls that face south absorb and reflect heat, which allows for exterior living spaces that are sheltered from the north winds and warmer for working outside in fall and the milder parts of winter. The heat stored in the walls and roofs slowly moves into the house overnight as the cold air outside pushes it inwards. This design also prevents overheating in most homes by shading them from the hot afternoon sun in the west.

The third floor room is used as a bedroom, which because it is one of the smallest and highest rooms in the home, makes them warmer in winter. This works because heat rises up the ladders from the floors below to warm the space from within, and the heat captured from the south-facing walls from the sun and the south-facing windows warms up the small space through the day.

The terraces are also used as a type of amphitheater from which to witness the seasonal ceremonial dances on the streetscape below.

Corner Windows #

The corner windows used on the Cultural Center are cousins to the traditions of using mica for windows at Acoma as well as to the corner windows at Chaco Canyon. The Cultural Center’s windows, however, are made of tan-colored mica to keep the UV light out and protect the museum collections. The corner windows at Chaco would not have been covered with mica, as they had an important purpose – they were aligned to a specific star or star cluster that rose in the night sky at a certain time of year. The rising of these stars as seen through those windows told the Chacoan astronomers that it was time for a special ceremony, when a certain animal would come through the area, or the planting of a crop.

Pintel Doors #

In the 1920’s, John Gaw Meem noted in his unpublished research on Acoma that a number of pintel or sanbullo doors still existed around the Pueblo. In pintel-style doors, one side extends into the header and threshold of the door to act as a hinge. We can check out the oldest form of this type of door when we enter the San Esteban del Rey Mission church – the sound of the 400+ year old door turning in its hinge is quite special. The Cultural Center uses wood, steel, and glass versions of these very cool doors.

T-shaped Doors #

T-shaped doors are common at Acoma, and they are similar in design to their Chacoan ancestors. However, Chacoan T-shaped doors almost seem to have been designed for people carrying large pots and baskets (We should note here that most archaeologists see the T-shaped doors as a symbolic trait… they are not consistently placed in great houses and frequently don’t line up with each other. We do not really know what the T-shape is actually for.) The T-shaped doors at Acoma have a much higher cross of the T. Acoma elders explain that this is so they can keep the seed pots stored on these shelves away from creatures that would get into and eat the seeds.

Acoma Fireplaces #

Where once upon a time, Acoma’s homes had open fireplaces in the center of the room with a skylight above in the roof, since Spanish times, venting and traditional fireplaces have been added. Acoma’s traditional fireplaces are distinctive however, as some variations have a wide firebox and vent-hood overhead, and others have a very tall vertical opening at the firebox.

Square Kivas #

Acoma is one of the Western Pueblos, which share unique characteristics that the Rio Grande Pueblos do not. One of those shared design characteristics is the use of square kivas integrated into the residential blocks. This is the same style as those at Zuni and Hopi. Rio Grande Pueblos utilize round kivas set apart from the residential areas.

Kivas are sacred chambers for praying together as a community. They are similar to churches.

Ladders #

Ladders are common throughout the village. The long pointed ends on Acoma’s kiva ladders are designed to pierce the sky and bring rain. Carved horizontal bars across some of these ladders represent clouds. Rain is always a sacred prayer for the Acoma people, who pray not just for themselves, but for all of us.

Stepped Divider Walls #

Stepped walls have been used as stairs to access Acoma’s third floors and their roofs for centuries. They also block winds at the entrances of the homes and hold the sun’s heat in winter so outdoor spaces are warmer. Next time you are outside and cold, sit in a corner of a stone or adobe wall facing the sun and you’ll see how this works!!

Craft #

Craft is one of the essential elements of culture that represents all communities in New Mexico. Native American communities have been designing beautiful objects for daily and ceremonial life for thousands of years here. They have almost always used local materials. Sometimes they traveled far away to find certain materials, or they traded with visitors from far away like Mexico! When the settlers arrived from Spain some 400 years ago, they brought their own traditions, which were modified for how hard it was to get materials here, and then both Native and Hispanic traditions were fused into new traditions. When the Americans came, the same thing happened again – everyone learned and borrowed from everyone. But always, throughout time, people have realized (sometimes too late) that the old ways are worth preserving too. So they re-introduce and re-learn their old, more pure way of doing things… the ways that that best represent who they really are, and who their people really are, without all the outside influences that watered them down. Acoma has reclaimed their language, which was almost stolen from them when it was banned in the early 20th century, and they are trying very hard to keep their culture alive by building on old and new forms of their cultural traditions of weaving, basketry, pottery, and building.

In the Cultural Center, Acoma’s craft tradition is celebrated with chimney pots, custom storytellers by Marilyn Ray, carved wood doors and furnishings with Acoma pottery and weaving designs, custom tiles with Acoma pottery designs by Brian Vallo, tiles with modern adaptations of pottery designs and storytelling elements by Acoma schoolchildren, hand-made traditional ladders, carved beams which feature Acoma corn and pottery designs, metal sculptural decorations of corn and pottery designs, metal grates with water symbols, a copper adaptation of a traditional Hispanic period tin ceiling, steel gates with pottery designs, and stone sculptures.

Today, Acoma artists share their wide range of craft traditions with the world. One such artist, Acoma fashion designer Loren Aragon, just won Phoenix fashion week with this collection for his company Aconav!

Carved Doors + Acoma Weaving #

Acoma’s weaving tradition, which was once carried out by talented male weavers, has been lost.

The doors in the cultural center are an ode to this lost tradition. They feature manta designs from some of Acoma’s lost weavings now preserved in museum collections.

Nichos #

Nichos are another of the universal elements of New Mexican design that come to us from both the Native American and Hispanic traditions. At Acoma, there are basically three types of nichos used:

- a small rounded nicho used for ceremonial purposes

- a medium nicho, sometimes which opens on two sides, which is used to put dry goods like seeds or grains in, then sealed over with plaster until it is time for those items to be used

- a medium to large nicho used for display of favorite objects, which may be cultural, natural, or manmade objects

In the Cultural Center, medium to large nichos are used for display.